Teasing the female passengers about the perils of the open sea was great fun, but once Horatio Merivale opened his mouth to laugh at danger, he wished he’d kept it shut. A storm dragged the Coventry under, and it was all the East India Company officer could do to rescue a terrified blonde from the merchantman’s foundering hulk. Still, the girl brought out the best in him, and the whole escapade seemed the start of a marvelous adventure.

Though she was but a simple lady’s maid, the recurring dream luring Anne Hazlett from England was grand — a turquoise seascape with a jade-carved island whose beaches beckoned. Yet she hadn’t expected to arrive on flotsam, be accosted by pirates, or have such an odd entourage. Indeed, the man who’d saved her was thrilled by their bad luck! “The Hand of Destiny” he called it. And looking into her eyes, the grinning Horatio made a promise: The current that swept them forward was irrestible, but he would see Anne to… The Wildest Shore.

The Wildest Shore

Chapter One

Aboard the English East Indiaman Coventry

Indian Ocean, 1811

“Sails on the horizon. Perhaps it’s pirates,” Horatio Merivale said to Miss Godwyn, widening his eyes in an affectation of terror.

Miss Godwyn giggled, and raised her chin as she tried to look out over the sea without rising from her seat on deck. “You should not jest about such things,” she said. “Anne, go look. I don’t believe there are any sails at all.”

Anne smothered her irritation and marked her place in her book with a ribbon. She’d been reading aloud to her mistress, and had been quite enjoying the story. Now that Mr. Merivale had joined them, though, she would have to sit and endure while he flirted with Miss Godwyn, complimenting her dark hair, her porcelain skin, her sky-blue eyes, her wit, her grace, her vast comprehension of world affairs, her remarkable musical talents, her way with injured animals and orphaned children, her trilling, tinkling laugh…

She set the book on her chair and staggered down the rolling and pitching deck to the lee rail, Mr. Merivale following close behind. She already had heard the lookout call his sighting of the sails to the first officer, an event which Miss Godwyn had failed to give notice.

“You see, that tiny square of white?” Mr. Merivale said, pointing. They were the first words he had ever directed to her. As a lady’s maid, she was not the social equal of an officer in the East India Company, and she assumed she was generally beneath his notice. She’d be surprised if he knew her name.

She followed his line of sight, and found the sail of which he spoke. She nodded.

“You see it?” he prompted, apparently not happy with a silent nod.

“Yes, sir.” From the corner of her eye she could see him looking down at her. He was a tall man, with dark brown hair and blue-green eyes that were set under down-sloping lids, giving him a mournful gaze that was at odds with his light-hearted manner. She had yet to see him without a smile playing around his lips, and she was not surprised that Miss Godwyn chattered constantly of him when they were alone. He possessed a certain charm, and if the gossip was to be believed, he had used that charm to break many a female heart.

There was one advantage to being beneath notice as a maid: she was enough of an outsider to clearly observe the follies of her betters. Miss Godwyn might fall under the spell of Mr. Merivale’s fawning flattery, but she, Anne Hazlett, could see the shallowness of the man, and the hints of his insincerity.

“You don’t seem worried. It could be that dastardly French privateer, Philippe Chartier. Aren’t you afraid?” he asked, that same smile teasing his lips.

“No, sir,” she said. It was infinitely more likely that the sail on the horizon was the East Indiaman Neptune than a pirate ship. The Neptune had left Cape Town at the same time as the Coventry, bound like them for India, and yesterday had fallen behind, dropping out of sight beneath the horizon in the same manner in which this ship was now appearing.

Mr. Merivale turned and leaned his back and elbows against the rail beside her, craning his head like a bird to get a better look at her face. She tucked her head down, the brim of her little jockey-style hat blocking her eyes from his view.

“No, you don’t look scared. Not of pirates, anyway,” he said.

He meant she was shy of him. She felt a flush of embarrassment heat her cheeks. She nodded once in his direction, and turned and staggered back up the deck to the awning under which Miss Godwyn sat. Her shoulders were tight with the sense of being watched, and she knew Mr. Merivale was observing her awkward retreat.

“Well?” Miss Godwyn asked. Her mistress’s voice was sharp, and Anne knew she hadn’t been expecting Mr. Merivale to follow her to the rail. The one thing Miss Godwyn could not abide was attention focusing on any woman but herself.

“There are sails,” Anne confirmed.

“What was Mr. Merivale saying to you?”

“Very little, Miss. He asked if I was afraid of pirates.”

Anne heard Mr. Merivale come up behind her, and Miss Godwyn’s face relaxed into a warm smile that was not meant for her.

“Are you trying to frighten my maid?” Miss Godwyn asked.

Anne picked up her book and resumed her seat, keeping the brim of her hat between her eyes and Mr. Merivale’s face. She examined his white pantaloons, the very latest fashion, with their straps that slid under each foot in its neat black shoe.

“Would a gallant man stoop to such a thing?” Mr. Merivale asked. “I frighten neither children nor servants — only ravishing young women sailing to exotic shores, in hopes that they’ll leap into my arms for safety.”

Miss Godwyn giggled. “You wouldn’t have had much success in frightening Anne, anyway. She is a veritable stone! She does not even startle when surprised.”

“Is that so?” Mr. Merivale asked.

Even through her hat brim Anne could feel him looking at her. She held motionless, realizing as she did so that she was acting the very stone that Miss Godwyn claimed. Her mistress had not yet deduced – and likely never would – that her stillness when surprised was not the result of bravery. Like a small animal, she froze when confronted.

Her mind skipped through modes of escaping this unwelcome attention – excusing herself with mention of a chore; suggesting that Miss Godwyn change for dinner – but speaking aloud seemed worse than sitting still and allowing the two sponge-brains to tire of her and move on to other topics.

“We could use someone like you in my regiment,” Mr. Merivale said. “Can you wield a sword?” he asked, to Miss Godwyn’s continued giggling. “Fire a gun? Ride a horse and chase down rebels, screaming your war cry as you go?”

Resentment simmered inside Anne. Did he think she was fair game for his jests because she was a mere servant?

She raised her narrowed, angry gaze to his. Their eyes met and he blinked, his head jerking back. Perhaps he was astonished to see that she was human and possessed of ears and understanding, and was not the emotionless stone Miss Godwyn believed.

His playful mouth unexpectedly settled into a somber line, the angle of it for once matching the mournful cast of his eyes. With the smile gone, there was something in his gaze that brought up a moment of empathetic sadness inside Anne. The man looked lost.

“My apologies,” he said softly to her.

“Tsk. Apologies? For what?” Miss Godwyn asked. “You don’t mind a little teasing, do you, Anne?”

Anne looked to her mistress, and smiled stiffly for her benefit, as if no harm had been done.

A cold gust of wind swept over them, and the bright sunlight beyond the awning dimmed, the decks going grey. Anne shivered, and Mr. Merivale stepped out from under their shelter and looked up at the sky.

“Perhaps it is a storm we have to worry about more than pirates,” he said.

Anne clasped her arms across her stomach, a sick feeling coming over her. It had nothing to do with the pitch and roll of the ship, and everything to do with the approaching storm. The shadow that had moved over them felt like the shadow of death.

* * *

“This isn’t going to be like the last storm, is it?” Miss Godwyn asked, her voice quavering. The ship creaked and groaned around them, the running footsteps of sailors heard overhead, as sails were reefed and hatches covered.

“Would you like a few drops of laudanum, so that you can sleep through it?” Anne asked. They were in their cabin, one of only four that were in the relatively luxurious roundhouse. The roundhouse was high in the stern of the boat, the poop deck overhead, the dining saloon and the captain’s cabin just down the passageway. They were fortunate in having portholes whose glass remained uncovered, free from the threat of waves in even the foulest of weather, although they could still hear the water rushing by below. Those who lodged in the great room the next deck down were less fortunate, the water not only rushing by but, from all reports, occasionally rushing in, even through the deadlights. Mr. Merivale was down there, as was Miss Godwyn’s brother, Edmund.

“Two or three drops. Perhaps four. I don’t like storms, Anne. I don’t like them at all.”

“We’ll come through all right,” Anne soothed, although her own belly was twisting with a sick certainty that this time such would not be the case. She’d been terrified through each and every storm they’d endured since leaving England some three months earlier, and had only keep her wits about her because the work of tending to Miss Godwyn kept her distracted from her fears.

But this time, it was less a mere fear than a queer certainty that disaster was roiling towards them across the turbulent seas. Since she was a child she had had a fear of dark, confined spaces, and being trapped in a cabin all through a stormy night, the ship in danger of foundering, was enough to make her want to down Miss Godwyn’s entire bottle of laudanum.

She brushed out another lock of Miss Godwyn’s black hair and rolled it in a rag, tying it to her mistress’s crown. It was nearly ten o’clock, and they would have to blow out the lamp soon. There was danger from French warships and privateers even here in the Indian Ocean, and the ship would be safest from attack if it were invisible in the dark, no lights shining from its portholes.

“What of those stories Captain Butters was telling, of ships breaking in half under the force of the waves?”

“Shhh,” Anne soothed, and tied the last roll of hair in place. She met Miss Godwyn’s eyes in the small mirror that was bolted to the vanity, the vanity in turn roped to staples in the floor. “I imagine he was amusing himself at your expense, is all. He wants to sink no more than we do, and will do his utmost to keep us afloat.”

Anne poured a small glass of water and mixed in three drops of laudanum, then added two more for good measure. Miss Godwyn took it from her and gulped it down.

“I wish we were there already. I don’t know how much more of this boat I can take,” Miss Godwyn said, handing back the empty glass. “Sometimes I feel quite certain that we will never reach India.”

“A month from now you will have forgotten all about this night. You’ll have parties to attend, and a basketful of suitors vying for your hand.” Even more powerful than laudanum was the mention of men for soothing and distracting Miss Godwyn.

“Do you truly think so? I thought Edmund had been exaggerating about how many eligible bachelors there are in India. I don’t suppose they have many opportunities for finding a wife, do they?”

“They’ll be tripping over themselves in their rush to woo you,” Anne said, feeling like a doctor pulling a favorite cure-all potion from his bag. ŒApply two mentions of men to patient. If patient does not immediately improve, apply third mention of men and offer compliments on the complexion.’

“As Mr. Merivale does now, like an eager puppy trying to please me. What do you make of him as a potential husband? His family has money, but I think perhaps I could do better. After all, he is twenty-five and still only a lieutenant, which does not say much for his ambition. And I gather he has a most frightful reputation for being a flirt. Edmund tells me he jilted a girl back home, and that in Cape Town there was at least one angry Dutch papa who was glad to see our ship leave port.” She sighed, pouting at her reflection in the mirror. “But still, he is the only amusement to be had on board. If I were not talking to him, I would have no one to entertain me but you and Edmund What a bore that would be!”

“Indeed.”

“Now don’t sulk, Anne. You know I meant nothing against your company, and I am very happy you chose to accompany me to India. Can you imagine me with an Indian maid? She wouldn’t understand a word I said! No, I could never find another who knows me as well as you do.”

Anne gave a tiny smile, and tried to let the words roll off her back. She knew they were, in Miss Godwyn’s self-absorbed way, kindly meant, and yet they had the effect of making her feel like a pillow or an old pair of shoes: an item present only for the comfort or use it could give, capable of no thought of its own. Miss Godwyn seemed to think that she had no inner life, and no interests beyond tending to Miss Godwyn herself.

Mama perhaps had been right, and she was not suited in her temperament for life as a lady’s maid. Mama said she had a mind too bright and a heart too sensitive to be happy being ordered about by another, especially when that other was a bird-wit like Miss Godwyn. Anne’s father was the gardener at Suffington Hall, Miss Godwyn’s home, so she’d had ample opportunity in her twenty years to watch the spoiled antics of Pamela Godwyn.

She’d had her own reasons for seeking the position of lady’s maid, and accompanying Miss Godwyn on her husband-hunting expedition to India. Mrs. Godwyn had been delighted to hire her to accompany her irresponsible daughter, assuming no doubt that Anne’s quietness bespoke dull reliability and lack of imagination.

Anne helped Miss Godwyn into her bed, holding the swaying cot steady as she climbed in. The narrow bed hung from ropes attached to hooks in the deck overhead. Anne was to have had an identical bed, immediately above Miss Godwyn’s, but her mistress had protested that it made for too much furniture in the room, and blocked the light from the porthole. The cot had been removed, and each evening Anne unfolded a hammock just as the sailors used, and strung it up on the other side of the cabin.

“I don’t know why Mr. Merivale was trying to talk to you, though, Anne,” Miss Godwyn said, her voice sounding sleepy as the laudanum took effect. The little frown between her brows smoothed out, as the drug worked its magic. “I’m sure it meant nothing. He was only amusing himself.” She yawned, and pulled her blanket up under her chin. “Tomorrow I’ll wear the blue silk. My eyes always look lovely when I wear the blue.”

“Sleep well,” Anne said, and started to put away the toiletries, Miss Godwyn’s brief musing on Mr. Merivale’s motives reviving questions of her own.

Why had Mr. Merivale tried to talk with her? Why had he noticed her today, when he never had before? It had surely been but bored mischief on his part, like Miss Godwyn said. Yet, she could not forget that moment when their eyes had met, and he had seemed to seen more to her than a mere maid, just as she had, for an instant, seen something other than an empty-headed fool in him.

The boat heeled sharply to port, and Anne stumbled into the small sofa that had been tied to the floor. She plunked down on the seat and clung to the arm. Miss Godwyn’s cot stayed level on its ropes, but the cabin tilted weirdly under it, giving the illusion that Miss Godwyn was about to be tilted out of her bed.

With one hand constantly gripping a piece of furniture for support, Anne got up and dug out her hammock, succeeding in attaching it to its hooks only after being thrown into the bulkhead twice, as the ship pitched. The pitching and rolling of the ship was getting worse, the movements more violent, and she was anxious to climb into the relative safety of the hammock.

A soft rap came on the door, and then she heard Kai, the Chinese cabin boy. “Lights out, Missy,” he said, and then moved on. He was little more than a boy, and often assisted the steward, his long black braid swinging across his back as he worked. He’d helped her as well, bringing water for laundry and washing, grinning at her with the high spirits of a youth who liked to have fun. She’d wanted to ask him about his home country, and how he liked working aboard an English ship, but hadn’t yet mustered the courage to ask such personal things.

Courage: that was something she was going to need a lot of tonight. She blew out the candle in its hanging lantern and climbed into the hammock, the maneuver well-practiced after the months at sea. She was still fully clothed, having removed only her stockings and slippers, a habit she’d taken up during the worst storms. It made her feel a little safer to be clothed.

The wind whistled through the shrouds above decks, the canvas of the sails ruffling and snapping as they were caught in a gust. She heard shouts and orders, and then a great crashing boom, making her flinch, her eyes open wide in the dark cabin as she listened with straining ears for sounds of distress. None came, and as the minutes passed she began to relax. Likely it had been something coming loose and falling to the deck, like one of the longboats. She only hoped it hadn’t been a sailor falling from a yardarm.

The movement of the ship was less noticeable in the hammock, and despite her nervousness she began to feel her eyelids grow heavy. The sounds of wind and water, and of creaking timber all began to blend together in a queer sort of lullaby, and she drifted off.

The dream came to her, as it had every night for as long as she could remember. She was flying through the sky, looking down on miles and miles of blue-green water, the sun bright overhead. In the distance was a bank of thunderclouds, immense, towering, majestic. She flew towards them.

As she approached she dropped down closer to the water, flying like the figurehead of a ship across the waves, her hair streaming behind her. Beneath the bank of thunderclouds was an island, a jade carving set upon the turquoise water, its inland mountains disappearing into the underbelly of the clouds. And somehow she knew that this was her island, her world, the place where she belonged.

The island grew larger, filling her horizon, and between the water and the green of the jungle she could make out the brown squares of small wooden houses, perched on stilts above the shore. Long, thin, brightly painted boats bobbed at their moorings, and a small brown child with black hair stepped out of one of the strange houses, onto the decking in front. The child shielded her eyes with her hands and looked out over the water, her gaze meeting Anne’s.

Lightning cracked out of the sky overhead, the juddering clap of thunder so loud that Anne could feel it in her chest. She jolted awake to the dark of the cabin, and to the sound of something immense being dragged across the deck overhead. Through the sounds of wind and slamming water she could hear the shouts of sailors, their voices tinged with panic and desperation.

Her own heartbeat thudded in her chest, the frantic calls of the sailors infecting her with their fear. She could see nothing, the cabin black as tar. The very air around her felt distorted, the sound of her own movements wrong. She reached out one arm, brushing it through the air, and hit her hand on a wall slanting above her to the left.

She felt it for a moment, confused, and then something heavy slid across it on the other side, and she realized it was the deck overhead that she was feeling. The ship was heeled so sharply to port that her hammock had swung to within two feet of the ceiling.

The ceiling came suddenly closer, and she heard the rush of a wave crashing over the ship.

Heeled this far over, the ship was in danger of being unable to right itself. In her mind’s eye she had a sudden vision of the sails dipping into the water, waves washing over them and holding the ship pinned upon its side.

There was the rhythmic chopping of an axe above, and more shouts. She remembered the crashing boom of thunder in her dream, and guessed it had been a mast that had cracked and come down. The sailors were trying to cut the lines and free the ship from the dragging weight.

Another wave washed over them, and the chopping sounds stopped. She listened, and they did not start again. The entire ship gave a great groan, the timbers cracking and popping.

Her body moved before thought had time to direct it. She flipped out of the hammock, hanging onto its ropes for support. Her feet found purchase on a wobbling board, and a moment of exploring told her it was the side of Miss Godwyn’s cot. She reached into the bed with her bare foot and jabbed at Miss Godwyn with her toes.

“Miss Godwyn! Wake up!”

Miss Godwyn mumbled, and shifted. Anne jabbed her again, harder, then shook the woman’s entire body with the sole of her foot, the fear coursing through her veins like quicksilver. “Miss Godwyn!” she screamed.

“What?” the young woman said, coming half awake. “Anne?”

“Wake up! We are wrecked!”

“Wrecked?”

Anne shook her again with her foot. “Up! Get up! We must get to the longboats!”

“Where… Anne? I cannot see. Anne?”

Anne lowered herself from the hammock to Miss Godwyn’s cot, which was tilted up against the outside bulkhead. “Here, I’m right here,” she said, as Miss Godwyn’s hands clamped onto her arm.

The cabin door above suddenly came open, lantern light spilling down on them.

“Pamela! God’s sake, get out of bed! We’ve got to abandon ship!” It was Edmund Godwyn, straddling the opening to the cabin, his feet on what had previously been walls.

“There’s water! Oh, Edmund, there’s water!” Miss Godwyn wailed, coming fully awake, and Anne felt the cold touch of the sea, seeping through the porthole and the floorboards. “I cannot reach you!” Miss Godwyn cried, gazing up at the doorway, so wrongly above their heads.

Anne’s eyes lit on the sofa, still roped to the staples on the floor. “The sofa, Miss Godwyn. We’ll climb up the sofa.”

“Anne, help her,” Edmund ordered. “God’s sake, girl, don’t just sit there!”

Anne shoved at Miss Godwyn, forcing her to stand on the tilted bulkhead. Water sloshed over her feet, and together they climbed over the tilted cot. Anne gave Miss Godwyn a boost up to the arm of the sofa, pushing on her rear end to help her up onto the small ledge, then pushing her again to climb onto the upper arm that was closer to the doorway.

“Edmund!” Miss Godwyn cried, stretching against what had been the floor and reaching up.

Edmund set his lantern down and got to his knees, bending down through the doorway and grasping his sister’s hand in one of his. He began to pull her up, Miss Godwyn’s feet scrambling at the deck for footholds that weren’t there.

Hurry, hurry, hurry, Anne mentally pushed her, the fear in her blood urging her to climb up herself, over Miss Godwyn if necessary, and escape this coffin.

Edmund got his sister to the passageway, Miss Godwyn sobbing audibly now. Her muscles weak with fear, Anne climbed up onto the top arm of the sofa and reached up.

“I’ve got to get Pamela to one of the longboats,” Edmund said down to her, picking up the lantern. “You’re strong, you can climb up.”

“No!” Anne cried. He vanished from view, and a moment later Miss Godwyn’s dangling feet disappeared from the doorway.

“Wait! Don’t leave me!”

The retreating lantern light cast a faint glow in the passageway, the doorway a dim rectangle, and then the light, too, was gone.

“Miss Godwyn!” she screamed. “Miss Godwyn! Don’t leave me!”

There was no answer, only the roar of the storm all around her, and the groaning death throes of the ship as timbers shuddered and began to break apart.

She was alone, and it was utter darkness.

The ship rolled, and she crouched atop the side of the sofa, clinging to the wooden legs. She stared stupidly at where she knew the doorway was, as if someone would appear and help her.

She heard the crash of a wave washing over the ship, and a moment later cold water poured onto her face from above. She shrieked, clinging more tightly to the legs of the sofa until the pouring water stopped.

She crouched, bracing herself with her extended arms against what had been the floor, her balance precarious. When the ship rolled slightly to starboard she stretched upwards against the floor, feeling for the doorway. The ship was hit by another wave, and a new rush of water poured over her hands and head in the dark, splashing salt water into her mouth and nose and making her gag as she hunched again on the side of the sofa, her body quivering now with the certainty of approaching death.

The ship lurched, and then her feet were covered in water. It wasn’t coming down the passageway this time: it was coming from beneath. The glass in the portholes must have broken, flooding the cabin.

Going down with the ship, was this how she was going to die? Drowned in a cab n, alone in the dark, left behind like an old shoe.

Images of her dream island suddenly flashed through her thoughts, white clouds and green mountains, more real than the blackness around her.

The dream had been what had lured her from the safety of home. Deep inside her was an absurd certainty that the island existed, and that it was waiting for her to find it and take her place on its wild shores. It was ridiculous: insane, even, to believe that such could be true, but deep inside she did believe it, and had hoped to somehow find the island by coming with Miss Godwyn to India.

The water rose up her shins. Had the dream meant nothing at all? Had it all been a way to pretend she was more special than a gardener’s daughter in a small, unimportant village?

“Bloody hell!” a man swore.

“Help!” Anne cried.

“Goddamn it, I knew I should have shipped on one of the newer boats!” the man griped, his voice coming closer.

“Help me!” Anne shouted, the water up to her thighs now. She carefully stood on the end of the sofa, leaning against the floor, reaching for the doorway.

“Here now, who’s there?”

“Down here! I cannot reach the doorway!”

“I can’t see a bloody thing!” There was a stumbling sound. “Christ! I almost fell down there myself!” he said. “Here, grab my hand.”

She batted her hand through the darkness, searching, then at last connected, the man’s hand warm and strong as it clasped her own. With a great heave she was suddenly up in the passage.

“We have to get out of here!” she said to the man, who was no more than a darker shadow among shadows.

“No, I was hoping to stay a little longer and enjoy the atmosphere,” the man said. He took hold of her arm and started dragging her with him towards the stern of the boat, away from the dining saloon where she had thought to exit. “What are you doing still in here? Don’t you know we’re sinking?”

“Don’t I… Where are we going?” she asked, stumbling along behind him, water now beginning to fill the passage as well, making their steps slow and heavy.

“The gallery. The saloon is flooded, everything has come loose, cannon, table, all jumbled in a heap – it’s impossible to climb through.”

Ahead there was a faint square of charcoal blue, only a fraction less dense than the blackness around them. It was the window in the door to the gallery at the stern of the ship.

“There won’t be any boats this way,” Anne said.

“That’s not an optimistic way to look at it.”

“It’s realistic!”

“You can stay here, if you’d rather,” he said, releasing her arm.

“No!” she cried, and grabbed hold of his coat. The water was rapidly rising, past her knees, inching towards her waist.

They were almost to the door. As they approached a wave hit the boat from the stern, smashing open the door and letting in a rush of water. Anne clung to the man as he clung to something on the wall, her feet slipping, her skirts pulling at her.

“That was fortunate,” he shouted, above the increased sounds of wind and water. “I was worried about getting the door open, and look! It’s been opened for us.”

Anne blinked at him in the darkness. He was beginning to sound almost cheerful. He took her arm and dragged her with him to the open doorway.

“Can you swim?” he asked, shouting to be heard over the roar of the storm.

“No!”

“Neither can I!”

“What will we do?” she cried.

“We’ll think of something,” he said, and boosted her over the side of the doorway and out onto the small porch that was the gallery.

Any protest she had was drowned in a mouthful of sea water as a wave poured over her. She scrambled for handholds and grabbed hold of the banisters of the gallery balustrade, across the narrow deck that she had once stood upon with Miss Godwyn, waving goodbye to England. With the ship tilted on its side the banisters made a ladder, and she climbed up them as high as she could go, feeling the man bumping into her from behind, urging her upward.

They were out in the open air now, the wind and water wild in the night around them, deafening and disorienting her. Only the faintest light came from the moon, blanketed in heavy clouds. The only thing Anne could see was the paleness of sails in the water a dozen yards away, and even that only for a few seconds at a time, as the waves continued to buffet and wash over the ship. They were slightly protected by the gallery itself, but that would not last long.

“There! We can float on that!” the man yelled.

She assumed he was pointing at something, but she couldn’t see what. “Where?”

“Ready?” he asked, wrapping his arm around her waist.

“No!”

“This is it!”

“No!” she cried again, but her hands lost their grip on the banister as he dragged her with him to the outside of the balustrade and then threw them both into the raging sea. They were immediately torn apart, and by instinct Anne kicked her legs and flailed her arms, the fear in her veins going wild, shooting panicked energy through her limbs. She didn’t know which way the ship was, or the fallen mast with its entrapping lines and sails. She didn’t know where the man was. Her skirts wrapped themselves around her kicking legs, and both rain and sea water slashed at her face, making her gasp and cough as she inhaled it, her arms still slapping futilely at the water that refused to hold her up.

A hand grabbed her by the back collar of her gown, and yanked her up against something hard. Her flailing arms hit the thing behind her, and with one arm she grasped hold, spinning round in the grip of the man, grabbing onto the smooth, rounded surface.

“It’s a spar,” the man shouted at her, from the other side of the floating timber. “Hold onto my arms.”

She dug her fingers into the material of his coat, and felt his own hands come around to grip her upper arms. Their arms made a bridge across the spar, easier to hold than the slippery log between them.

“What do we do now?” Anne shouted.

“Now?” the man asked, and laughed. “We hold on!”

A storm like this could last for days. She doubted she could last an hour, clinging to the spar. She looked in terror around her at the tossing darkness, then closed her eyes and wedged her cheek between her shoulder and the wood, and again the image of the island came to her, like a green promise of life from across a sunlit sea. She dug her fingers a little more tightly into the man’s coat sleeves.

Time went by, creeping in painful inches. The man let go of her left arm, and her head came off the spar. “What are you doing?” she cried, panicked.

“Hold on. Can you do that for a minute, without my help?”

“Why? Where are you going?”

“Just hold on! Can you?”

“Yes,” she said, her voice weak and lost in the storm.

“What?”

“Yes!” she screamed at him, terrified.

“Good girl!” he said, and then he was gone.

Her weight felt suddenly heavier on her arms, her hold less secure. The spar rose and fell with the huge waves, rolling under her grip, and it was desperation only that gave her the strength to continue to cling to it. The cold of the water was slowly sapping away her energy. Each second was filled with disappointed hope as she waited for the man’s return, each shadow and shifting patch of dark becoming his head in her imagination, then disappearing as nothing. Where was he? Would he come back at all? She didn’t want to be alone. She wouldn’t be able to hang on, alone.

Then suddenly he was beside her, reaching around her with a length of rope. “I’m going to tie you to me and to the spar,” he shouted against the wind.

She nodded, even though she knew he could barely see her. Her relief at having him back had stolen her voice. It took him several minutes of fumbling to get her secured, and then finally she relaxed her aching arms and rested against the support of the rope. He climbed over the spar to the other side, and tied himself in place across from her.

In time the sky gradually began to lighten, shapes coming out in shades of grey. The wind became slightly less fierce, and Anne began to drift off to sleep.

“Ahoy!” her saviour shouted, startling her awake. “Ahoy there!”

“Ahoy!” came an answering cry from somewhere behind her. “Who’s there?”

“It’s Merivale,” the man called. “And Miss Hazlett.”

Anne gaped through the twilight at him. Mr. Merivale, the fawning, foolish puppy: he had been the one to save her. And he knew her name. In her befuddled state, she could not decide which was the more unbelievable.

“Ulrich, here. And Kai, and Ruut.”

Anne turned to watch as a strange, lumpy shadow slowly moved towards them, disappearing in the darkness of a wave trough and then suddenly looming in silhouette above them, on a crest. Then she realized that they were not moving towards her: she was moving towards them. There was a rope stretching between the spar and the lumpy shadow, and someone from the other end was pulling on it, the rope going taut and snapping out of the water a few inches from her shoulder.

The lumpy shadow drew closer, and Anne saw that it was made up of chests, barrels, broken timber, and miscellaneous bits of wood furniture, all haphazardly lashed together with rope. Three men were atop the makeshift raft, working together to pull the rope tied to the spar.

“You must have been tangled with us all night,” one of the men said, a young, slender fellow with pale blond hair. “We did not know you were there.”

“Thank God you found us now,” Mr. Merivale said, then climbed over the spar to Anne’s side, and began to unlash her.

“You’ve got to get out of the water,” he said to her.

She nodded as if she understood, but her thoughts were foggy. When she was free of the rope and tried to pull herself up onto the raft, her arms refused to lift. “I can’t,” she said, exhausted now past even fear. She felt the need to cry tight in her throat, and yet even that emotion was distant from her, a physical sensation lodged in a body that was separate from herself.

“Give hand, Missy,” Kai said from above.

“Don’t give up now, Anne,” Mr. Merivale said from beside her. He grasped her by the wrist and raised her hand for her. Kai’s small hands closed around hers, and then another of the men joined him, taking her other hand. Together they hauled her out of the sea, Mr. Merivale pushing from behind.

She flopped across a sea chest, her body feeling too heavy to move. She was vaguely aware of the men helping Mr. Merivale up onto a nearby barrel, and then, as if the hard, rough chest were the finest mattress of feathers and down, she fell deep asleep.

Reviews :: The Wildest Shore

“What a find! The Wildest Shore is really different from anything else I’ve read lately. The pirate is not a handsome, devil-may-care swashbuckler. The ladies’ maid is not bosom friends with her sweet-tempered employer. The tropical island paradise features leeches, headhunters, and bugs the size of your fist. Different is good.

…The result is a book that’s romantic, sexy, and a lot of fun. I enjoyed spending time with these characters; I think you will, too. I’m on my way to find Lisa Cach’s backlist.”

Grade: B+

Jennifer Keirans

__________

“Seafaring adventures and romance on the high seas and in the hottest tropical jungles – The Wildest Shore is a breathtaking, comedic, and exciting road trip of a romance indeed. And as always, this book is unlike any of Ms Cach’s previous books in premise and plot. Maybe I best go get a few more copies for my friends in Sabah as well. We need more authors who dare to be different in the genre.”

Rating: 88

Mrs. Giggles

“It is not the exhilarating ‘Indiana Jones’ type adventures that make THE WILDEST SHORE such an exciting romance, but Ms. Cach’s hero, who is willing to give the woman he loves everything she desires–not material trappings, but freedom and the chance to be who she was meant to be. That is a gift every woman dreams about and one that is often ignored by writers. So cast aside civilization and allow yourself to be swept away into a new kind of women’s fantasy.”

Kathe Robin

__________

“I cannot begin to describe how very intriguing this book is. I highly recommend this highly adventurous book. I will also be pulling all of the rest of Lisa Cach’s other books out of my huge pile of books and putting them on the very top!”

Kathy Boswell, Managing Editor

__________

“It has been a long time since I have read a novel that was as fun as this one. The dialogue is quick-witted and entertaining and the characters a sheer delight.”

Elizabeth McConnell

__________

“FIVE STARS!”

As with her previous book, The Mermaid Of Penperro, the characters each had their own personality and were easy for me to care for. Full of adventure, romance, and a touch of humor, this story is a winner!”

Detra Fitch

__________

Background Notes with Photos :: The Wildest Shores

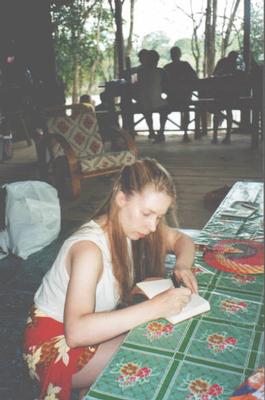

Trekking the Headhunter Trail in Borneo, where I constantly checked for leeches on my legs.... and occasionally found them.

Researching The Wildest Shore took me on one of the greatest adventures of my life: to the island of Borneo, in southeast Asia! I spent three weeks in the Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak (they were filming Survivor I on an island off Sabah while I was there), doing everything from climbing Mt. Kinabalu to staying in a long house with the descendents of head hunters, walking (carefully) through a cave filled with millions of bats and their guano, shrieking as insects the size of birds splashed into my dinner, picking leeches off my legs, traveling by long boat up a river during a rain and lightning storm, and learning to treasure my flashlight and private stash of toilet paper.

I also got to put to use an older adventure, that I undertook while a college student. I spent six weeks on a schooner with 23 other students, sailing the Caribbean while learning about nautical science, oceanography, and marine biology. Or that was what I was supposed to be learning: mostly I concentrated on vomiting over the lee rail (never the windward!), and wondered whathad possessed me to sign up for such torture.

I am a wimpy adventurer, who likes a warm freshwater shower at least once a fortnight and a bed that does not bounce me like a hackeysack. I did love my turns at the helm, though, and being on bow watch in the middle of the night, searching the dark sea for the lights of oncoming boats.

Your hard-working romance-writer at a jungle camp, with filthy hair. The only place to bathe was "Crocodile Lake," where I eventually did, despite the constant fear that a crocodile would swim through the murky water and snap off my foot.